“I am without hope. It's a good starting point. From there, we can address how civilisation – humans co-operating in large numbers – may continue rather than collapse as the impacts of global heating continue to reveal themselves. We must not be ruled by fear or be distracted by the comfort of consumption as we try to reduce the extents of these impacts.”

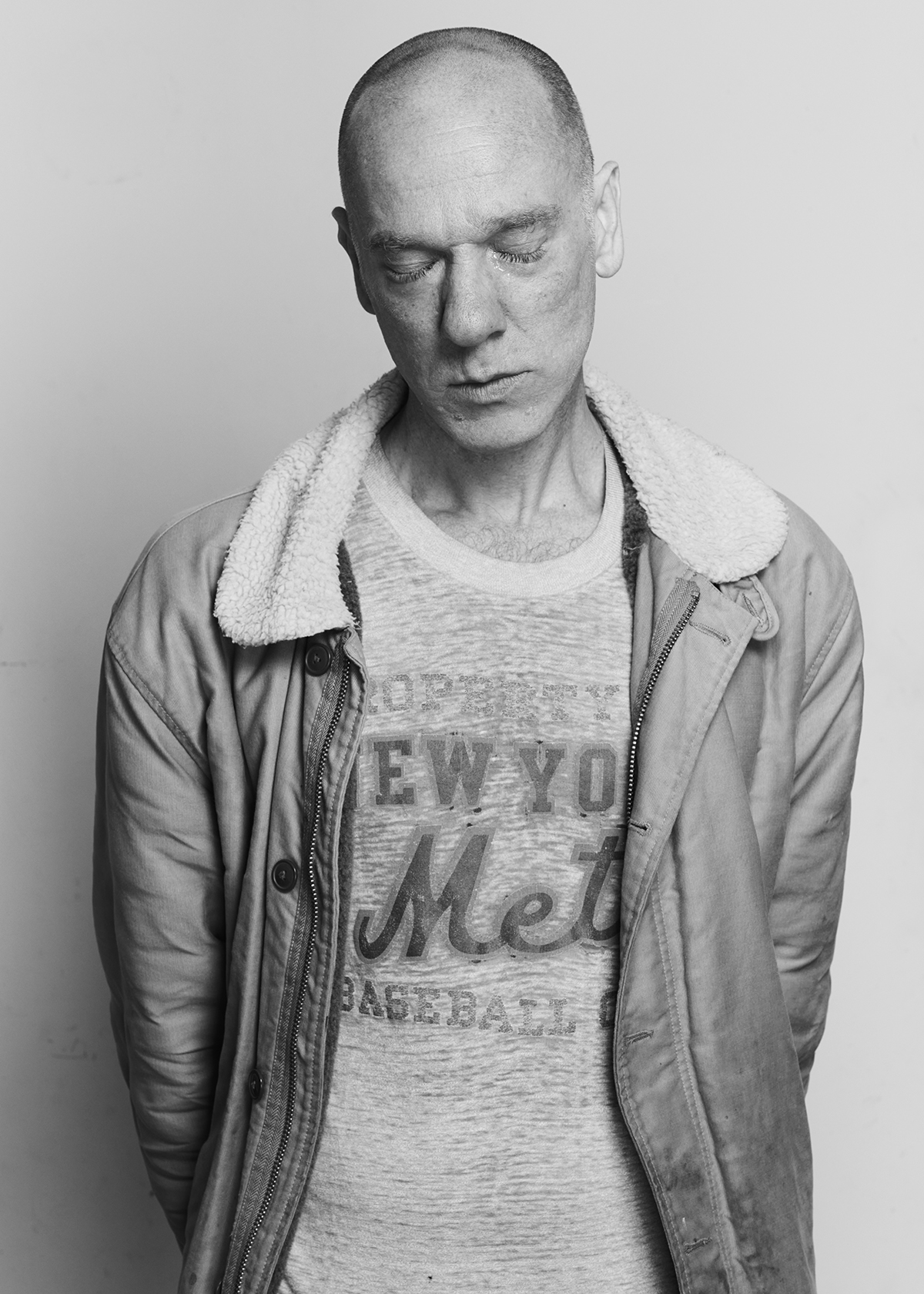

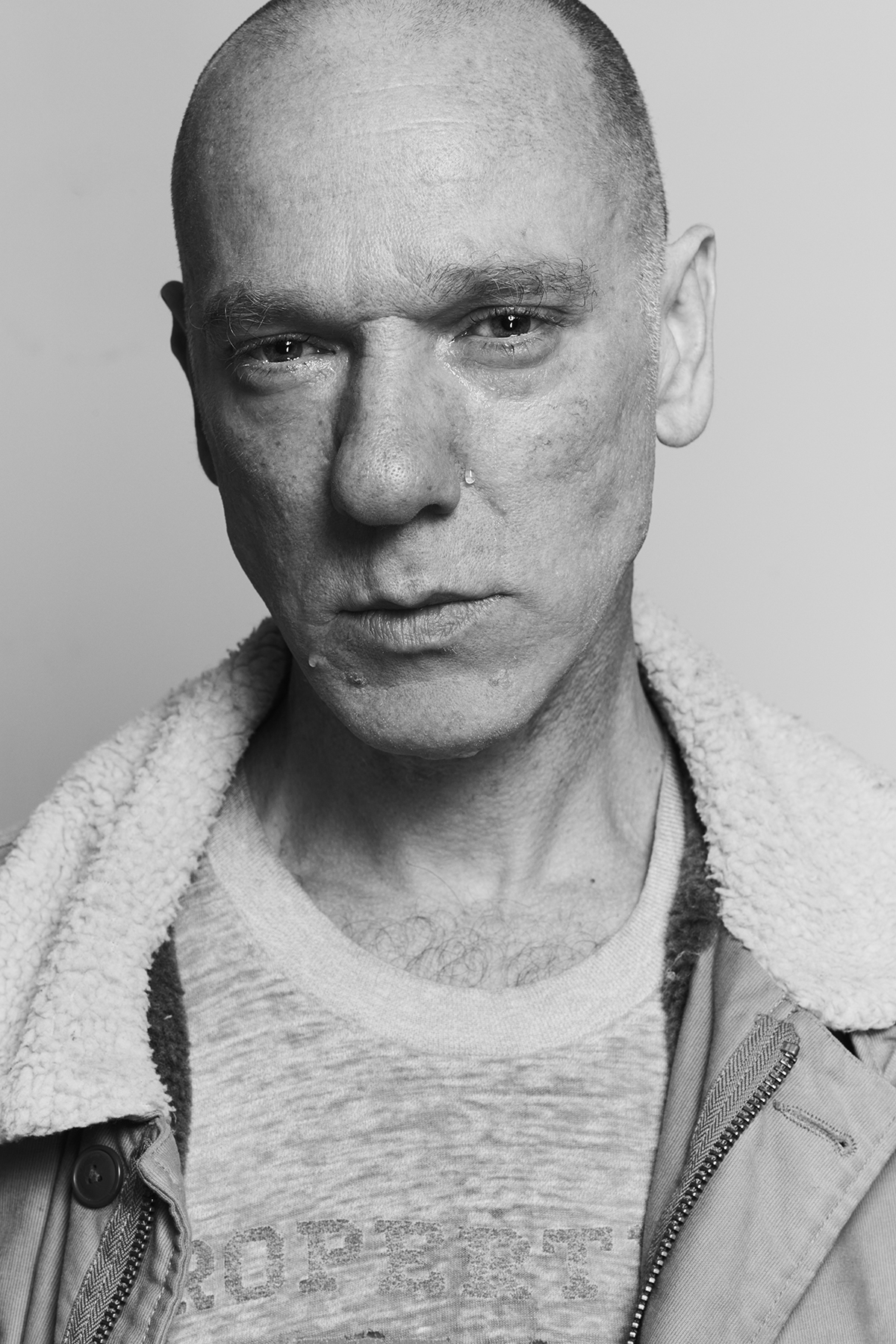

DAVID

Meet David

David is an academic, teaching post-graduate architecture design with an emphasis on timber construction techniques and adaptive re-use strategies. He uses his role as a teacher to shape the mindset of future generational Architects - this is his form of activism.

Text: Beth Mark & Sandra Freij

Photography: Sandra Freij

David is also a photographer who collaborates with architects with whom he shares a critical and cultural understanding of practice. Additionally, David has built a body of photographic work that he exhibits when opportunities arise. In 2018, he published his first book ‘Still Beautiful’, a large format monograph containing twenty years of work, an attempt by him to reveal the complexity and depth of the entanglements of humankind and the world.

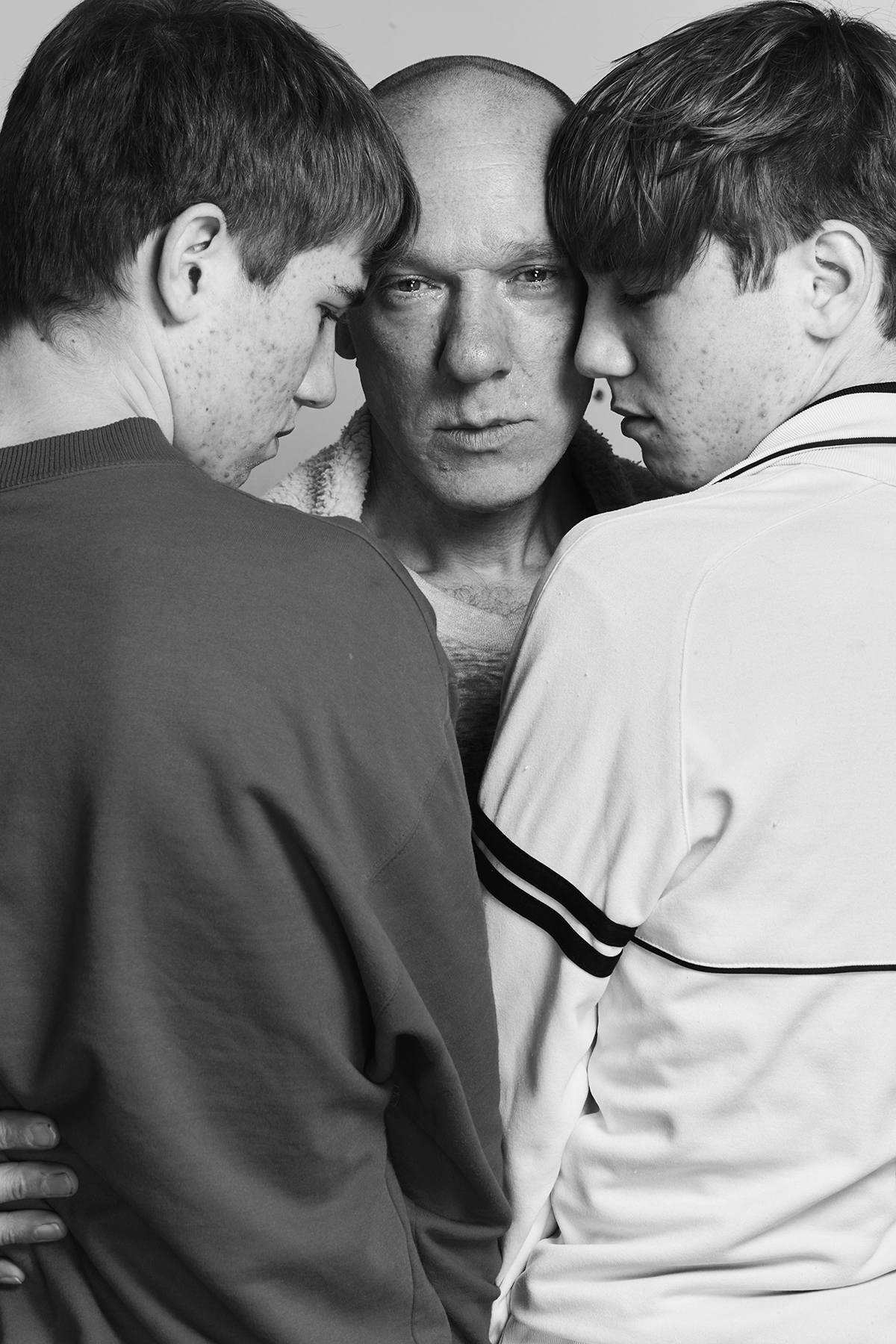

We meet David in his timber frame home near East London’s Victoria Park, where he lives with his partner Lucy and their twin boys, both sixteen going on seventeen, “like Liesl von Trapp in the Sound of Music.” he says with a smile.

I have known David for two decades. Over the years I’ve often found myself at his kitchen table, discussing ideas about photography and hearing about his latest assignments, travels and exhibitions. It was through his photographic work, and what were often charged conversations, that I first started grasping the essence of climate breakdown, the urgency of which was, for a long time and much to David’s despair, lost on me. For a long time I considered myself having more urgent issues to deal with…where to live, whom to love, what to do with my life. I once screamed at him in a pub when he tried to encourage our gathering to share the roast instead of ordering one each. David hates food waste. I was pregnant. It was a collision of forces with exceptional magnitude.

David is my inspiration to take action. If everyone had a friend like him, I have no doubt that the world would be in a better place.

When approached with the subject of climate change, like so many people, he finds it difficult to talk about on a personal level; “it hurts”, he adds, so instead, he prefers to focus on the need for systematic change driven by government.

As the magnitude of the climate crisis intensifies, he reflects on his relationship with the issue, “I first became aware of the phenomenon in the late eighties but only really understood its impacts a little later in 1992, the year of the Rio Earth Summit. Like many others, I have tried to understand the subject at macro and micro scales, scientifically, philosophically and economically, but as the range of its causes and impacts are so broad – it is what Timothy Morton calls a ‘Hyperobject’ – it is difficult to see its edges, understand it as whole. James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis is the nearest we have to that.”

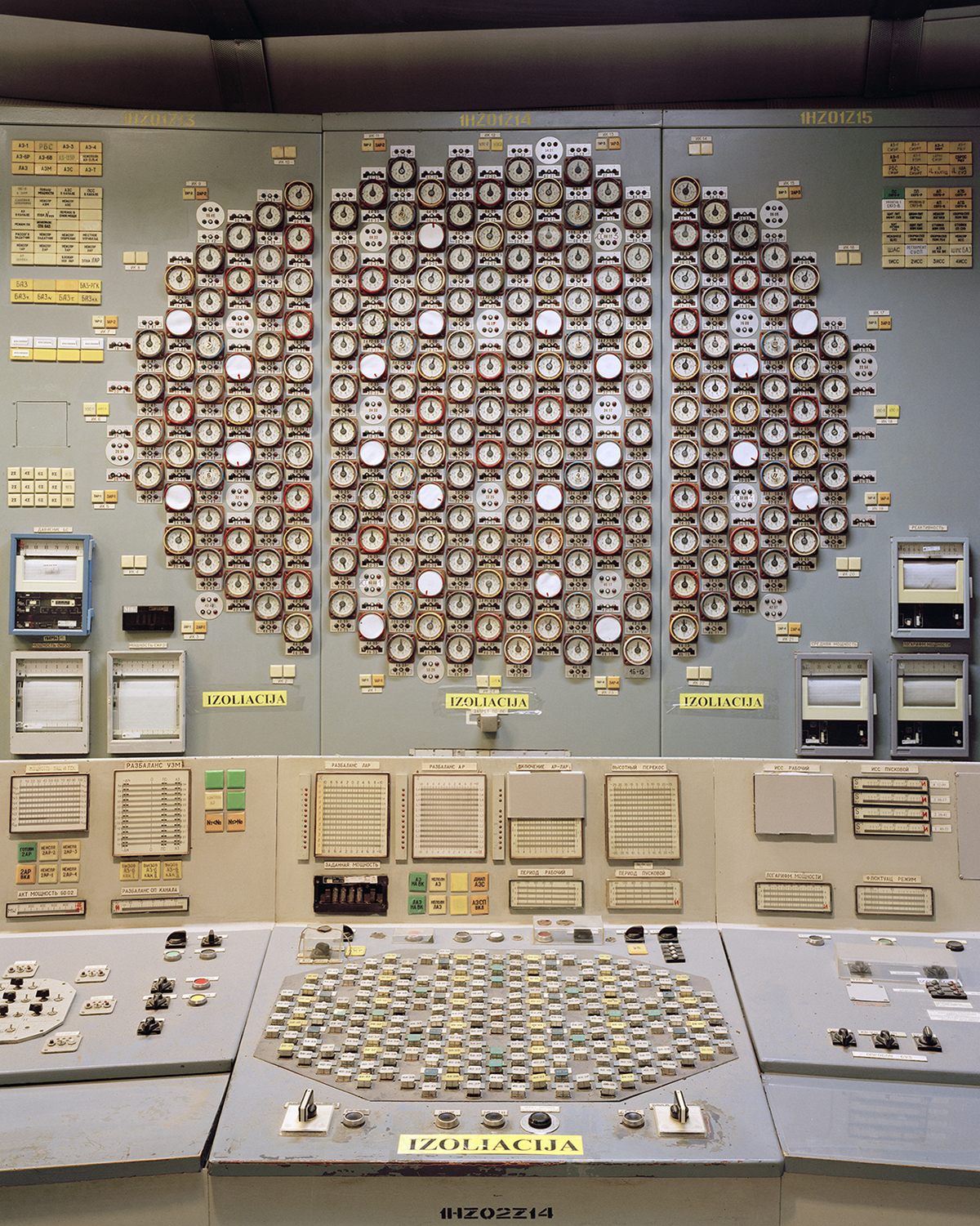

David Grandorge, “Svalbard” from his book

“STILL BEAUTIFUL”

After decades of exploring the complexities, David discusses some of the constraints he believes governments must work through to mitigate climate change.

The first constraint (highlighted as the most pressing issue) addresses the energy industry.

David explains, “We need to decarbonise the energy industry immediately and in its entirety. We need to decouple capitalist economy from energy production to have any real success with this. Unfortunately, due to vested interests - the future value of pensions, shares and hedge funds are wrapped up in it – the process is very slow moving.”

Signs of change are showing here with Pension funds divesting from fossil fuels, last year in Denmark and Sweden, followed by announcements by the Norwegian Sovereign fund and more recently this year by the UK’s National Employment Savings Trust. But change is woefully slow; in the event of pensions taking a 100% fossil free investment strategy it would channel billions into sustainable energy. But unlike the hopeful headlines we see daily in the tech section of the newspaper, David is quick to point out renewable energy is no panacea in itself.

With the ever-growing demand for energy, David expresses the importance of our need to require and use less. His home is unheated throughout the year opting for extra layers as part of his own drive to acclimatise to the needs of energy reduction. David’s images of a decommissioned nuclear power station in Lithuania and oil shale waste hills in Estonia describe our efforts past and present to keep up with our ever-increasing energy needs.

“You can pay for as many insulation programs as you want and help bring down the price of micro-renewables, but in the end, people have to use less… the current demand is not sustainable. Now, because we have less, does not mean that our lives will be less, that's what people have to understand - this shift in consciousness is really important. I have learnt how to live with less by being in places like Jordan where people have 5 litres of water a day compared to 160 here…people managed and many, if not all, still live rich lives.”

Our discussion around human requirements naturally progressed to consumerism. This is often overlooked when it comes to the notion of carbon footprint and net carbon production. The old adage ‘out of sight out of mind’…and off the balance sheet, rings loud here. Nationally there is blank space in the column that accounts for all the waste produced by other nations in order to service our domestic ‘needs’.

David Grandorge, “Zokniai VI” from his book

“STILL BEAUTIFUL”

David explains his take on where both regulation and consumer habit require paradigmatic shift when it comes to production and consumption in their relation to climate destruction.

“First, we have to look at where materials come from and how they are extracted. Are they a renewable resource or finite? We should understand the energy used, the toxins produced by the manufacturing processes and what happens to the run offs. The polluting of watercourses is a huge problem in the slave camps of Asia where we buy things that are thrown away in a high capitalist consumer culture without anyone thinking of the consequences locally, both for the humans and the landscape.”

When asked, what do you think is holding societies back from adjusting to more sustainable, less damaging practices? David replies,

“I think the question for many is ‘can we have an economy when we have left these entrenched practices behind?’ And the answer is ‘of course we can.’ We can create energy infrastructure that doesn't emit carbon dioxide. We can have an economy that re-uses and upcycles and that could employ hundreds of thousands of people. So for those that are concerned with over-consumption, there are other solutions. The most important thing for me is to reuse everything - for as long as possible. And in there is an economy. There is distribution; there is storage, and there is also work for people in making the exchanges. The material consequences of consumption could be greatly lessened if we make these changes."

After years of exploring ‘less damaging’ cultures and learning about global heating, David incorporates many low impact practices into his daily routine and is content in living a light touch lifestyle.

“In everyday terms, I have eschewed space heating (I can afford to buy warm clothes) and eaten less (by following the Kate Moss diet – cigarettes and coffee). I have never driven a car nor bought a plastic bottle of water and so on.”

David keeps himself informed through reputable resources to adjust his understanding and behaviour as new information arises.

He explains, “It is something that informs the practice of everyday life… I continue to read the words of people smarter than me in order to understand how we might make nature and culture contingent again.”

Finally I ask David ‘What is your main hope for the future?

“I am without hope. It's a good starting point. From there, we can address how civilisation – humans co-operating in large numbers – may continue rather than collapse as the impacts of global heating continue to reveal themselves. We must not be ruled by fear or be distracted by the comfort of consumption as we try to reduce the extents of these impacts.”

In his essay Reconnaissance that ends the book ‘Still Beautiful’, there’s a poignant quote from artist Gerhard Richter, summarising his underlying belief that only by relinquishing the distracting practices of consumption can we navigate past the tradition of woefully inadequate response in the light of human’s destructive wasteful practices.

“The realisation of climatic damage and the prospect of climatic catastrophe creates fear, but no effective action towards changing it. On the contrary, fear is only a sign of our certainty that we can change nothing, and to palliate our fear we go in for displacement activities that make not the slightest possible difference; just like our ancestors, who faced up to nature, armed with nothing but prayers and sacrificial offerings.”

1 Gerhard Richter, “The Daily Practice of Painting”, MIT Press, 1998, p.242

1

1 Gerhard Richter, “The Daily Practice of Painting”, MIT Press, 1998, p.242

THE THREE TAKE-HOME STATEMENTS:

People will have to use less - this does not mean our lives will be less fulfilling.

Use your role as a teacher, parent, co-worker to influence upcoming minds.

Focus on re-using to stimulate the economy - another way is possible

Links to further reading

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎ David’s book - Still Beautiful

https://www.lyncharchitects.com/books-writing/still-beautiful/

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎Timothy Morton - Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the end of the world

Paperback

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎James Lovelock -Gaia

Paperback

London 2020